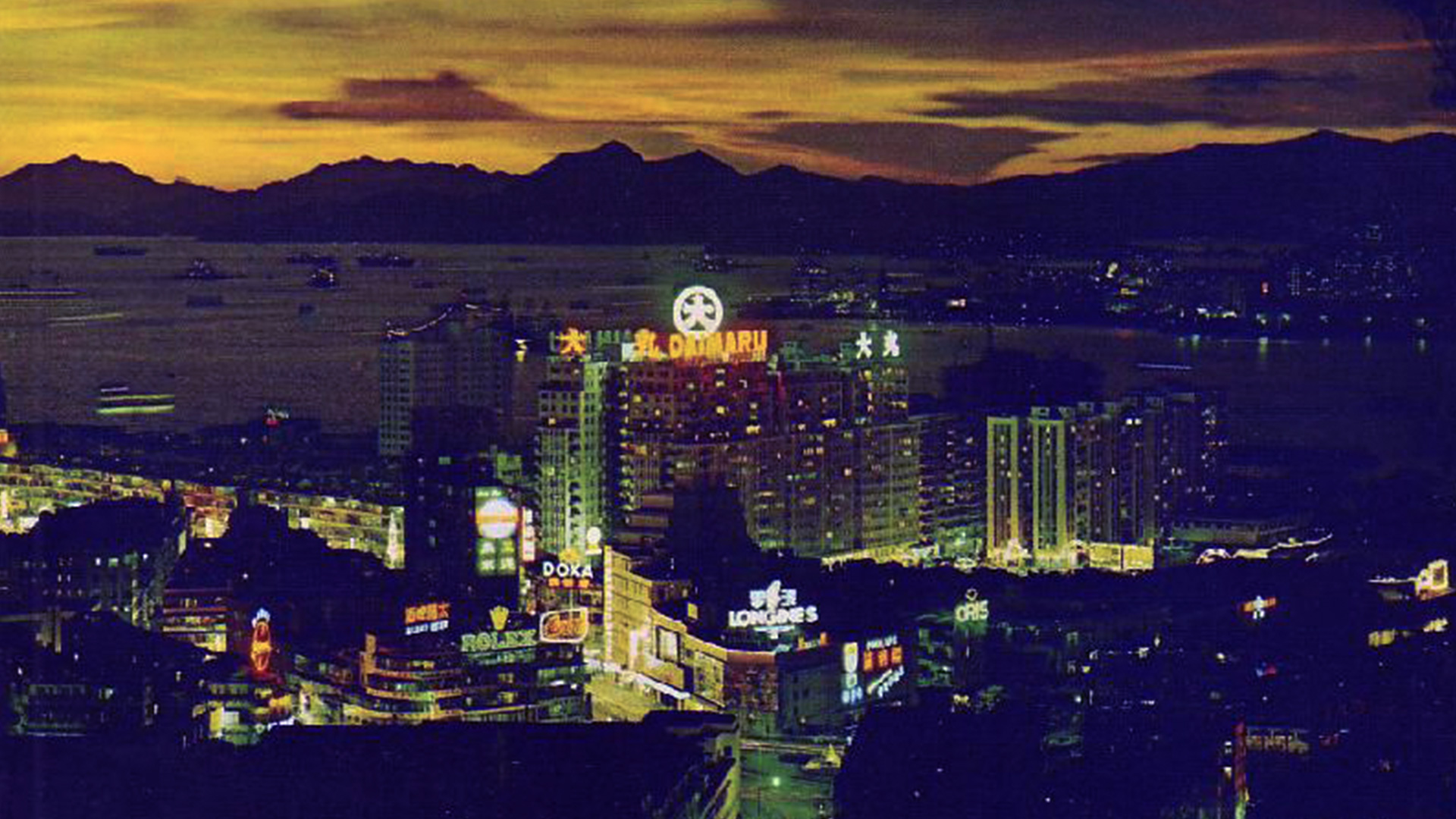

That’s certainly not true anymore. Hong Kong is a fast changing city, but Causeway Bay has changed even more rapidly than most other neighbourhoods. It has evolved from an industrial area to a shopping hub, with community organisations, residential areas and increasingly upmarket offices thrown into the mix. With every step of the neighbourhood’s transformation, a little bit of the past is left behind, creating a melting pot unlike any other.

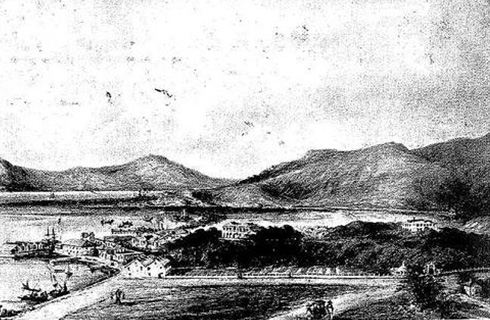

Some of these traces are less obvious than others. Few traces remain of the original wave of development that brought Causeway Bay into Hong Kong’s urban fold. Back then, Causeway Bay lived up to its name – it was a broad inlet known in Chinese as Tung Lo Wan, or Copper Gong Bay. To the south was the old Hakka village of Tai Hang; to the west, a hill that tapered out into a peninsula that came to be known as East Point.

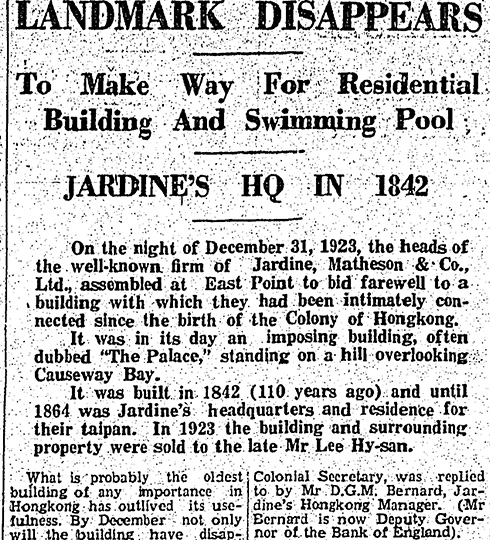

East Point was one of the first pieces of land sold off by the British colonial government when it was established in 1841. A Canton-based trading firm called Jardine, Matheson and Company bought it for £565 and built an office on the waterfront. The next year, it built

an ornate headquarters known as the Palace on the nearby butte, which was named Jardine’s Hill after the company.

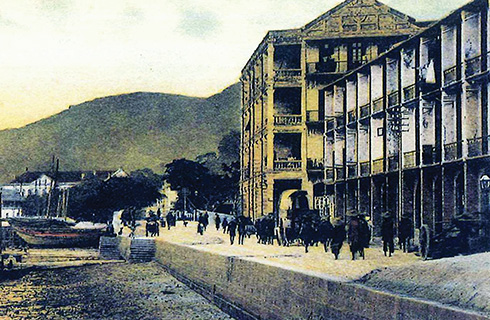

Jardine’s chief, known as the taipan — derived from the Cantonese word for “big boss” — took up residence in the Palace, and over the next few decades, he watched as East Point became Hong Kong’s first major industrial area. Shipyards, warehouses and factories were built, including Hong Kong’s first sugar refinery, which opened in 1878. It was followed two years later by Hong Kong’s first ice factory ; until then, ice had been imported all the way from New England. Hong Kong’s coins were produced on Royal Mint Street, which long ago disappeared from the map.

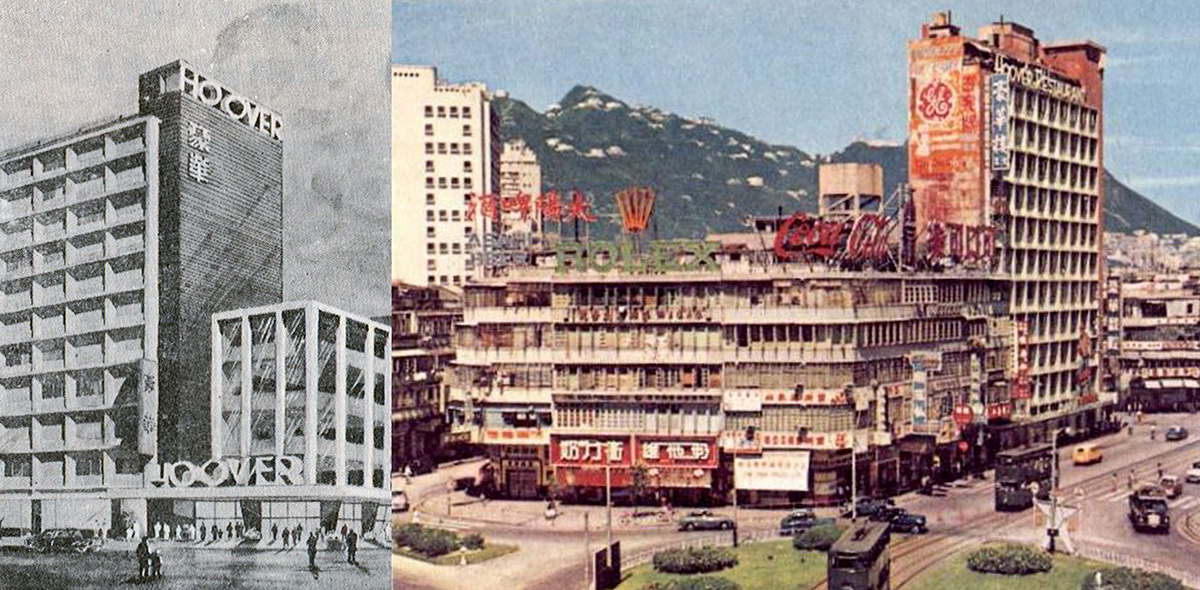

This industry attracted plenty of other businesses. One of Hong Kong’s first street markets emerged on Jardine’s Bazaar, which ran between East Point and Jardine’s Hill, and Chinese tenements were built along a small web of commercial and residential streets to the west, including Percival Street, Sharp Street and Russell Street. Hong Kong’s first public park opened nearby, on the site of the present-day Craigengower Cricket Club.

That’s certainly not true anymore. Hong Kong is a fast changing city, but Causeway Bay has changed even more rapidly than most other neighbourhoods. It has evolved from an industrial area to a shopping hub, with community organisations, residential areas and increasingly upmarket offices thrown into the mix. With every step of the neighbourhood’s transformation, a little bit of the past is left behind, creating a melting pot unlike any other.

Some of these traces are less obvious than others. Few traces remain of the original wave of development that brought Causeway Bay into Hong Kong’s urban fold. Back then, Causeway Bay lived up to its name – it was a broad inlet known in Chinese as Tung Lo Wan, or Copper Gong Bay. To the south was the old Hakka village of Tai Hang; to the west, a hill that tapered out into a peninsula that came to be known as East Point.

East Point was one of the first pieces of land sold off by the British colonial government when it was established in 1841. A Canton-based trading firm called Jardine, Matheson and Company bought it for £565 and built an office on the waterfront. The next year, it built an ornate headquarters known as the Palace on the nearby butte, which was named Jardine’s Hill after the company.

Jardine’s chief, known as the taipan — derived from the Cantonese word for “big boss” — took up residence in the Palace, and over the next few decades, he watched as East Point became Hong Kong’s first major industrial area. Shipyards, warehouses and factories were built, including Hong Kong’s first sugar refinery, which opened in 1878. It was followed two years later by Hong Kong’s first ice factory ; until then, ice had been imported all the way from New England. Hong Kong’s coins were produced on Royal Mint Street, which long ago disappeared from the map.

This industry attracted plenty of other businesses. One of Hong Kong’s first street markets emerged on Jardine’s Bazaar, which ran between East Point and Jardine’s Hill, and Chinese tenements were built along a small web of commercial and residential streets to the west, including Percival Street, Sharp Street and Russell Street. Hong Kong’s first public park opened nearby, on the site of the present-day Craigengower Cricket Club.

Jardine had a firm grip on East Point – indeed, on the whole of Hong Kong. It was arguably the most influential company in the early colonial era, and its taipan was the “central personage of Hong Kong society,” as he was described by the New York Times. Whenever the taipan sailed into East Point from a stint overseas, he was greeted by a gun salute – something normally reserved for high government officials. A cannon is still fired every day at noon from the foot of Cannon Street in honour of this tradition.

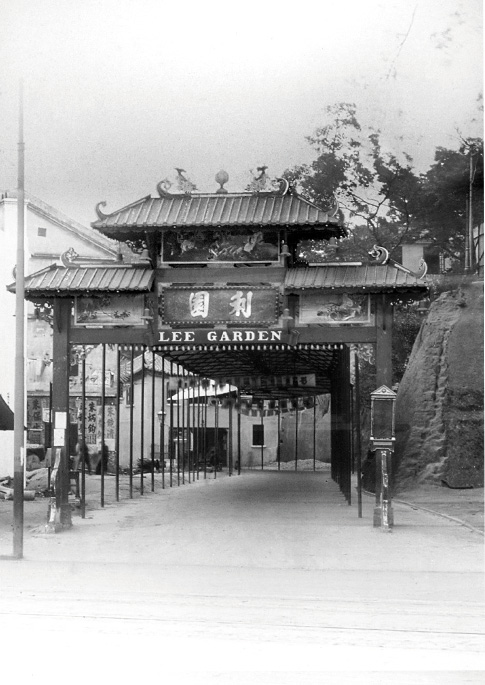

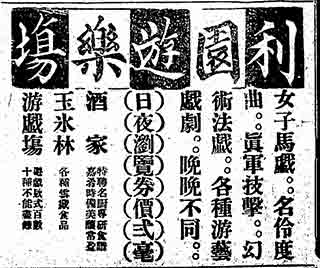

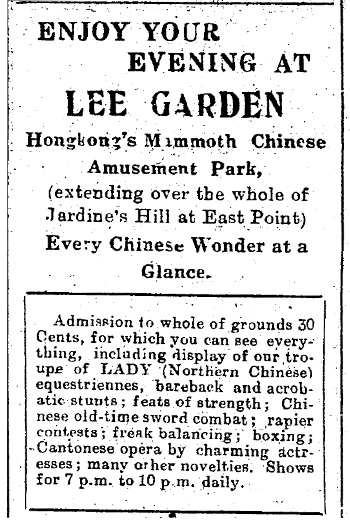

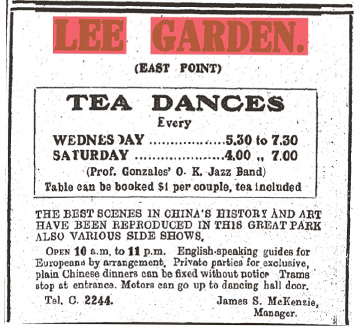

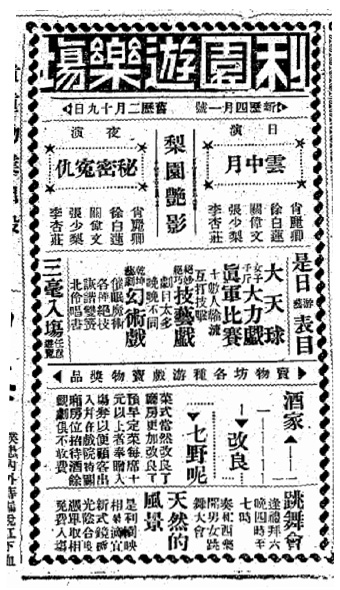

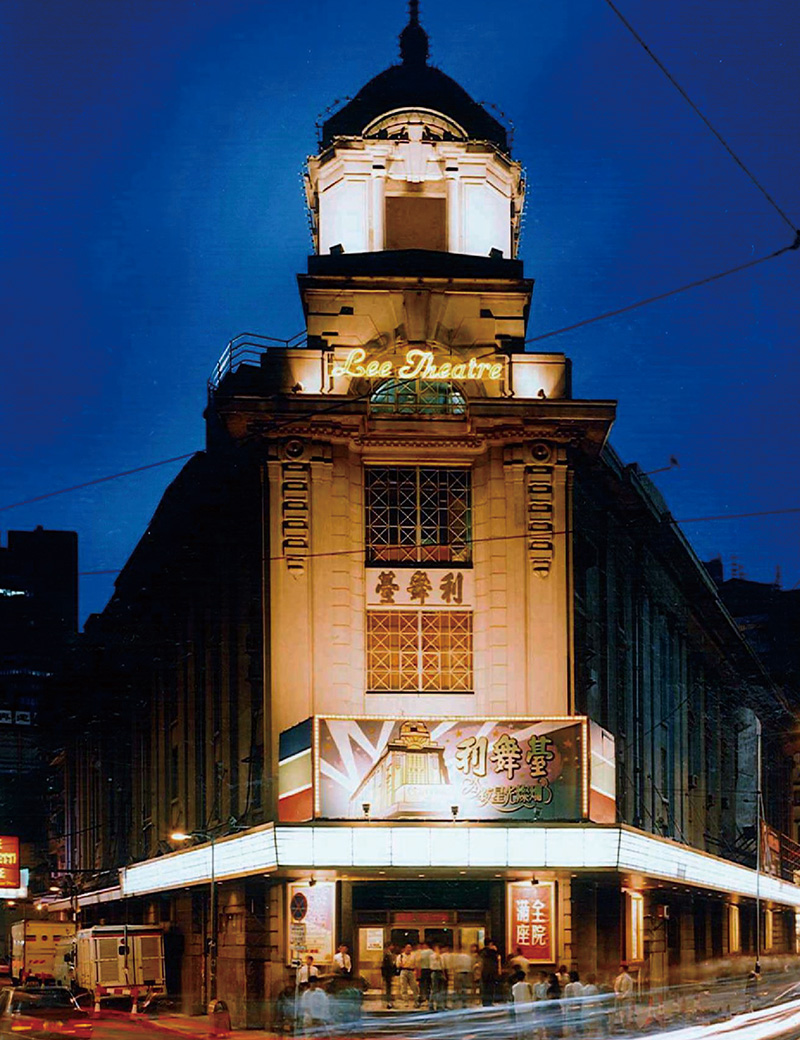

But the British conglomerate knew a good business opportunity when it saw one. In 1923, when American-educated businessman Lee Hysan, who was born and raised in Guangdong, offered to buy Jardine’s Hill for HK$4 million , the company happily sold its property, including the 1842 mansion once inhabited by the taipan. Lee had wanted to level the hill for development but cost and bureaucratic issues led him to shelve the plans. He decided to open an amusement park instead. He called it Lee Garden.